Can a single word decide a verdict? In law, it often does.

Law is a language — not merely in a metaphorical sense, but in its very structure and function. Every statute, judgment, or contract is expressed through words that carry meaning, intent, and authority. Yet, words are inherently ambiguous. Their meaning depends on context, culture, and interpretation. This is where jurisprudence and linguistics intersect, creating a fascinating field of inquiry into how legal meaning is constructed, communicated, and contested.

This blog explores the philosophical and emerging dimensions of the interplay between jurisprudence and linguistics, examining how linguistic theory influences legal interpretation and how language shapes the very foundation of law.

Jurisprudence: The philosophy and theory of law. Linguistics: The scientific study of language and its structure.

1. The Linguistic Turn in Jurisprudence

In classical jurisprudence, law was seen primarily as a set of rules created by sovereign authority — as in John Austin’s “command theory.” However, the 20th century witnessed a “linguistic turn” in philosophy and law. Thinkers like Ludwig Wittgenstein, J.L. Austin, and H.L.A. Hart emphasized that meaning is not intrinsic to words but depends on how they are used in specific contexts — or what Wittgenstein called “language games.”

J.L. Austin’s “speech act theory” shows that utterances like “I pronounce you guilty” are not just descriptive but performative — they enact legal consequences.

H.L.A. Hart’s The Concept of Law (1961) illustrates this shift. Hart argued that legal rules have an “open texture” — their meaning cannot be fixed absolutely, as new situations constantly arise that were not foreseen by lawmakers. Thus, judges must interpret words not just literally but purposively, considering the intent and purpose behind the law. This marked the beginning of linguistic jurisprudence, where interpretation became central to legal philosophy.

Table:

| Theory | Key Thinker | Legal Implication |

| Command Theory | John Austin | Law as sovereign command |

| Open Texture | H.L.A. Hart | Law requires interpretation |

| Language Games | Wittgenstein | Meaning depends on use |

2. Law as a System of Signs and Symbols

From a linguistic viewpoint, law is a semiotic system — a network of signs (words, symbols, gestures, documents) that represent norms and authority. The French semiotician Ferdinand de Saussure distinguished between signifier (the form of a word) and signified (the concept it represents). In law, this distinction becomes vital.

For example, the word “property” can signify ownership, possession, or control, depending on the statute or context. Similarly, the word “reasonable” in “reasonable doubt” or “reasonable care” cannot be defined precisely; its interpretation depends on judicial reasoning, societal standards, and linguistic context.

In Indian tort law, “reasonable care” varies across contexts — from medical negligence to consumer protection — illustrating linguistic fluidity.

Thus, legal meaning is not static but relational — it evolves as the interaction between law, language, and society changes.

3. Interpretation: From Text to Context

Interpretation bridges jurisprudence and linguistics. Every act of legal interpretation — whether by judges, lawyers, or lawmakers — involves translating linguistic signs into legal meaning.

There are two dominant schools of thought in this regard:

- Textualism (Literal Approach):

This approach insists on the primacy of the text. Judges like Justice Antonin Scalia in the U.S. emphasized that courts must rely on the ordinary meaning of the text, not on the intent of legislators. - Purposivism (Contextual Approach):

Here, the focus shifts from mere words to why the law was enacted. Courts consider legislative intent, social purpose, and moral context. Indian courts, for instance, often favor this purposive interpretation under Article 141 of the Constitution, where Supreme Court decisions serve as binding precedent.

In Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, the Indian Supreme Court interpreted “amendment” not just textually but in light of constitutional identity — a purposive leap.

Linguistics helps reveal that no text can be fully self-explanatory. Meaning arises from pragmatics — the context, intention, and social use of words. Hence, jurisprudence relies on linguistic tools like syntax (structure), semantics (meaning), and pragmatics (use) to decode legal texts.

| Approach | Focus | Example Jurisdiction |

| Textualism | Ordinary meaning | U.S. (Scalia) |

| Purposivism | Legislative intent | India (Article 141) |

4. Philosophical Dimensions: Law, Language, and Truth

From a philosophical standpoint, the connection between jurisprudence and linguistics raises profound questions:

- Can legal meaning ever be objective?

- Is interpretation merely discovery, or is it a creative act?

- Do judges “find” law or “make” it through linguistic construction?

Legal philosophers like Ronald Dworkin argue that judges interpret laws as part of a moral narrative, giving coherence to the legal system — a process deeply tied to language and reasoning.

Meanwhile, Critical Legal Studies (CLS) scholars highlight that legal language often hides power relations and biases, making interpretation a site of ideological struggle.

“Judges are authors in a chain novel, interpreting law to maintain coherence.” — Ronald Dworkin

Therefore, language is not just a neutral medium in law — it is a tool of power, persuasion, and politics.

5. Emerging Dimensions: AI, Linguistics, and Legal Interpretation

In today’s digital era, the interplay between jurisprudence and linguistics is expanding through computational linguistics and artificial intelligence. Legal databases, machine translation, and AI-driven judgments increasingly depend on linguistic algorithms to interpret legal texts.

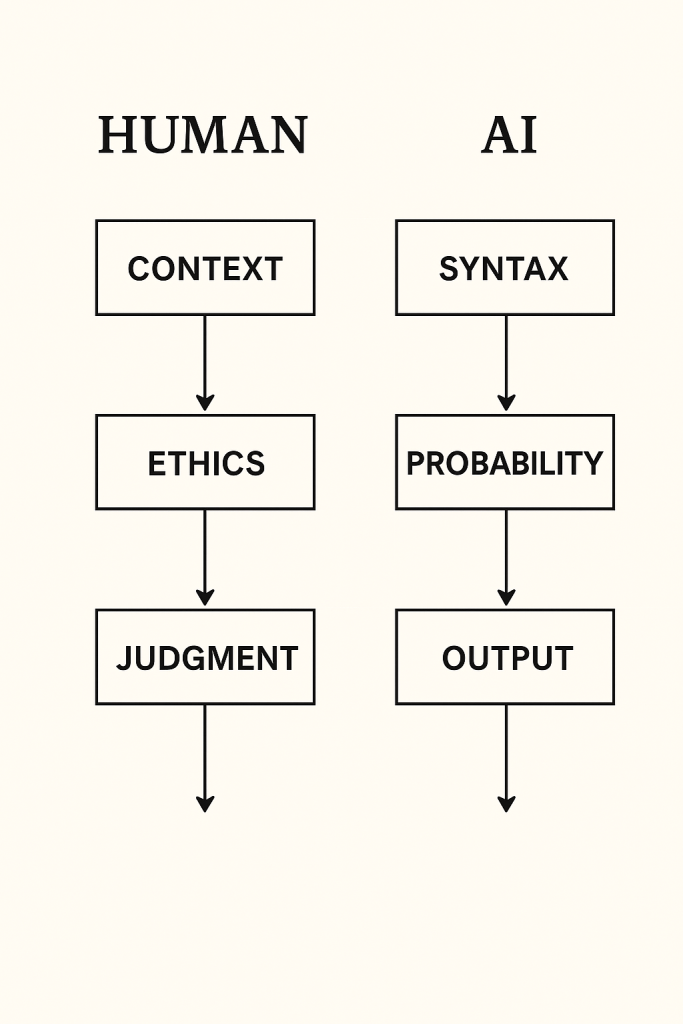

However, machines interpret language differently — they rely on syntax and probability, not moral or purposive reasoning. This raises ethical and jurisprudential questions:

- Can AI truly “understand” legal meaning?

- What happens when algorithms interpret ambiguous terms like “public interest” or “reasonable care”?

Emerging research in Legal Natural Language Processing (Legal NLP) aims to teach AI systems contextual reasoning. Transformer-based models like BERT and GPT are now used to parse legal syntax and semantics, but struggle with purposive nuance. Yet, the human element of interpretation — empathy, ethics, and intent — remains irreplaceable. The linguistic nature of law ensures that interpretation can never be fully mechanized.

6. Conclusion

The interplay between jurisprudence and linguistics reveals that law is not a closed logical system but an open, evolving discourse shaped by human language. Legal meaning depends not only on words but also on interpretation, intention, and societal context.

Philosophically, this connection emphasizes that understanding law requires understanding how language constructs reality. In the end, law is not just written — it is read, interpreted, and lived through language.

References

- Hart, H.L.A. The Concept of Law. Oxford University Press, 1961.

- Dworkin, Ronald. Law’s Empire. Harvard University Press, 1986.

- Austin, J.L. How to Do Things with Words. Oxford University Press, 1962.

- Saussure, Ferdinand de. Course in General Linguistics. McGraw-Hill, 1966.

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Philosophical Investigations. Blackwell Publishing, 1953.

- Scalia, Antonin. A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law. Princeton University Press, 1997.

- Bhatia, Vijay K. “Legal Discourse: Opportunities and Threats for Corpus Linguistics.” International Journal of Law, Language and Discourse (2010).

#Jurisprudence #LinguisticsAndLaw #LegalInterpretation #PhilosophyOfLaw #LegalSemiotics #LegalLanguage #LawAndMeaning #LegalTheory #AIinLaw #PhilosophicalDimensionsOfLaw #EmergingLegalTrends #LanguageAndJurisprudence #LegalLinguistics #DrGaneshVisavale

Discover more from Dr. Ganesh Visavale

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.