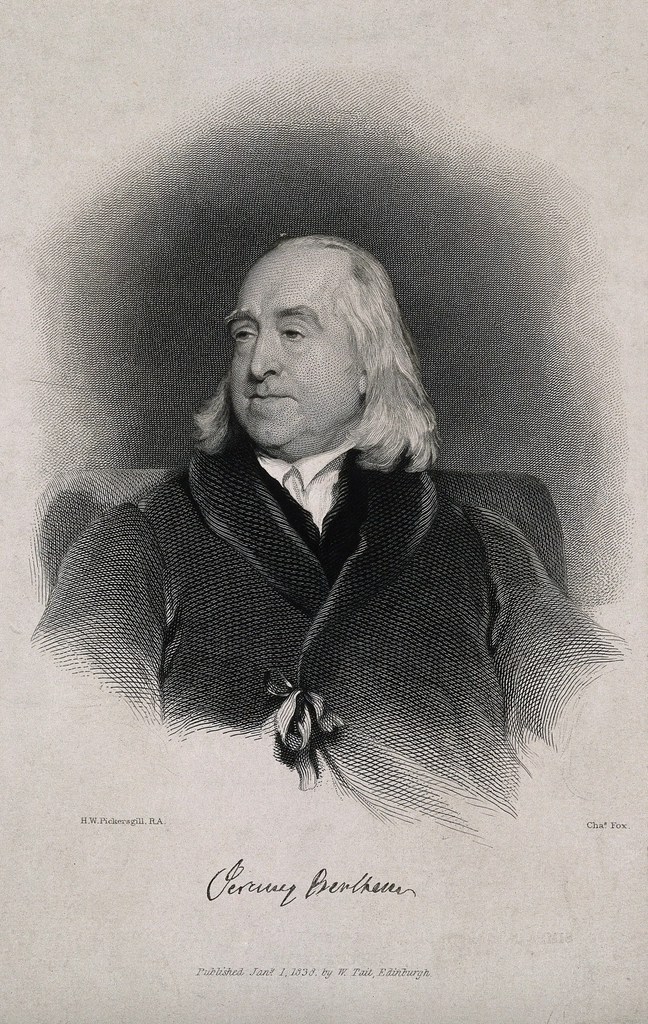

Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) remains one of the most influential figures in the history of jurisprudence. His ideas reshaped how society views law – not as divine command or abstract morality, but as a social instrument designed to maximize happiness and welfare. Bentham’s philosophy of utilitarianism – the principle of “the greatest happiness of the greatest number” – laid the foundation for modern legal reforms, codification of laws, and the concept of justice rooted in public welfare. Even today, his legacy continues to shape legal thought, legislative drafting, and the moral basis of governance across democratic nations.

But how well does Bentham’s vision hold up in today’s complex legal landscape – where justice, rights, and welfare often collide?

Bentham’s Core Theory: Utilitarianism and the Purpose of Law

At the heart of Bentham’s jurisprudence lies utilitarianism, which evaluates actions and laws based on their utility – how much happiness or pain they produce for society. Bentham viewed law as a rational tool for social engineering. According to him, laws should not be derived from religion, custom, or metaphysics, but from reason and experience that promote human welfare.

Bentham believed that human beings are governed by two “sovereign masters” – pleasure and pain. Thus, the purpose of law is to align individual interests with social good by discouraging harmful acts through punishments and encouraging beneficial ones through rewards. This practical and result-oriented approach to legislation made Bentham one of the earliest advocates of what we now call policy-oriented jurisprudence.

Evaluation of Bentham’s Theory

Bentham’s ideas were revolutionary for his time. He sought to transform law from a chaotic mix of judge-made decisions and customs into a systematic, codified, and accessible structure. His rejection of natural law theory – which claimed laws derive from morality or divine command – was groundbreaking. Bentham called natural rights “nonsense upon stilts,” arguing that rights must come from laws enacted by legitimate authority.

His theory emphasized:

- Rational Legislation: Law should be made systematically, not through arbitrary precedent.

- Codification: Laws must be written clearly for public understanding and consistency.

- Legal Positivism: The validity of law depends on its source (legislature), not its moral content.

However, critics argue that Bentham’s pure utilitarianism often overlooks individual rights. If the majority’s happiness justifies every law, it could lead to the oppression of minorities. Furthermore, reducing all human motives to pleasure and pain is considered oversimplified by modern psychologists and moral philosophers.

Bentham’s Jurisprudence: Strengths vs. Critiques

| Strengths | Critiques |

| Rational, systematic approach to law | Overlooks emotional, cultural, and moral complexity |

| Codification for clarity and accessibility | Risks rigidity and loss of judicial discretion |

| Utility as a moral standard | May justify unjust outcomes (e.g., sacrificing minority rights) |

| Legislative supremacy | Undervalues local customs and common law evolution |

Despite these criticisms, Bentham’s utilitarian framework gave rise to modern legal positivism and inspired reformers to make laws more scientific and democratic.

Bentham’s Influence on Modern Law

1. Codification and Legal Reform

Bentham’s advocacy for codification inspired numerous legal systems worldwide. His followers, such as John Austin, carried forward his mission. The Indian Penal Code (1860) drafted by Lord Macaulay was profoundly influenced by Bentham’s utilitarian and codification ideals. Similarly, Bentham’s emphasis on clarity and accessibility shaped the evolution of administrative and criminal law in Europe and beyond.

Today, almost every modern constitution reflects Benthamite ideas of clarity, accountability, and legislative supremacy. Codified civil, criminal, and commercial laws in countries like India, France, and the United States trace their intellectual roots to his reforms.

2. Law and Economics

Modern law and economics scholars, such as Richard Posner, revived Bentham’s utilitarian ideas by linking law with social welfare and efficiency. The cost-benefit analysis used in public policy decisions reflects Bentham’s belief that laws should aim for the greatest net social benefit.

3. Human Rights and Democracy

Although Bentham criticized natural rights, his utilitarian view indirectly promoted democratic governance. His idea that government exists to serve the greatest happiness of the people evolved into welfare state principles. Institutions such as public health, education, and environmental regulation embody Bentham’s belief that law should enhance collective welfare.

Though Bentham denied natural rights, his utilitarianism laid the groundwork for rights-based governance by emphasizing collective welfare and institutional accountability.

4. Criminal Justice and Punishment

Bentham’s “principle of utility” influenced modern penology – the philosophy of punishment. He proposed that punishment should only be as severe as necessary to deter crime, making him a pioneer of the reformative theory of punishment. Many modern systems emphasize rehabilitation over retribution, reflecting Bentham’s humane approach.

Bentham’s ideas didn’t just shape legal codes – they redefined how law interacts with economics, governance, and human rights. Yet Bentham’s legacy is not without its philosophical tensions. Critics have long debated whether utility alone can sustain a just legal system.

Critical Reflections on Bentham’s Legacy

While Bentham’s rational and utilitarian vision modernized legal systems, his critics question the moral limitations of utilitarianism. For instance:

- Neglect of Justice: Utility cannot always ensure fairness; sometimes, justice demands protecting minority rights even against majority happiness.

- Absence of Emotional and Cultural Dimensions: Bentham’s mechanical view of pleasure and pain ignores moral sentiments, traditions, and cultural factors influencing law.

- Moral Relativism: If utility is the only test, harmful acts could be justified if they produce more pleasure for the majority.

Philosophers like John Stuart Mill refined Bentham’s utilitarianism by introducing qualitative distinctions between higher (intellectual) and lower (sensual) pleasures, thus restoring moral balance. Despite such modifications, Bentham’s practical contributions – legal reform, codification, and democratic governance – remain unchallenged.

Bentham’s Continuing Legacy

In today’s context, Bentham’s philosophy is embedded in constitutionalism, legislative policymaking, judicial reasoning, and administrative accountability. His insistence on transparency, measurable outcomes, and codified laws resonates with the modern ideals of good governance.

International institutions such as the United Nations, which focus on maximizing human welfare through measurable indicators (like the Human Development Index), indirectly follow Bentham’s utilitarian principle. Even artificial intelligence ethics and public data regulation are now being discussed in utilitarian terms of maximizing social benefit while minimizing harm – a true testament to Bentham’s lasting intellectual influence.

Can law be both empirically grounded and morally sensitive? Bentham’s legacy challenges us to find that balance.

Conclusion

Jeremy Bentham’s contribution to modern law is more than theoretical – it is foundational. His utilitarian philosophy transformed jurisprudence into a science guided by reason, reform, and measurable welfare. Though often critiqued for neglecting moral depth, Bentham’s vision of law as a tool for social happiness continues to guide legislators, reformers, and judges in shaping fair and effective legal systems. His legacy lies not merely in what he theorized, but in how the world continues to practice his principles in pursuit of justice, clarity, and the common good.

References:

- Bentham, Jeremy. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789).

- Austin, John. The Province of Jurisprudence Determined (1832).

- Hart, H.L.A. Essays on Bentham: Studies in Jurisprudence and Political Theory (1982).

- Macaulay, T.B. Report on the Indian Penal Code (1837).

- Mill, John Stuart. Utilitarianism (1863).

#JeremyBentham #Utilitarianism #LegalPhilosophy #ModernLaw #LawReform #Codification #Jurisprudence #BenthamLegacy #LegalPositivism #WelfareState #LawAndEconomics #LegalTheory #BenthamVsMill

Discover more from Dr. Ganesh Visavale

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.