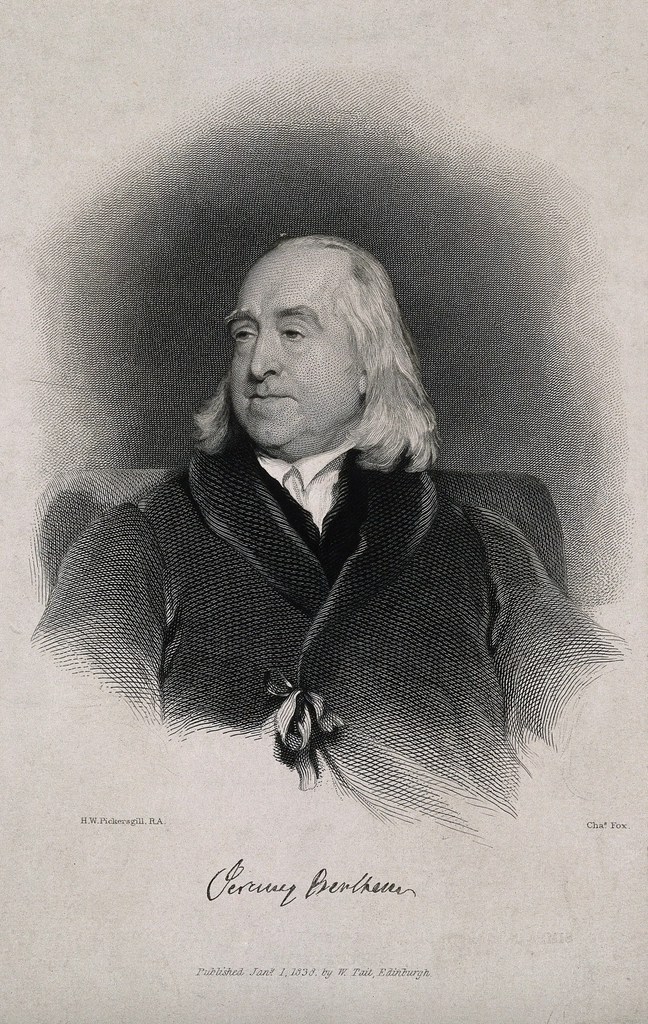

Jeremy Bentham, often regarded as the father of legal positivism and founder of utilitarian jurisprudence, revolutionized modern legal thought by introducing the idea that law should serve the greatest happiness of the greatest number. His philosophy turned law from a moral and theological institution into a rational and scientific one. However, Bentham’s jurisprudence has not been free from criticism. While his utilitarian approach greatly influenced legal reform, codification, and administrative efficiency, it also faced sharp critiques for its mechanical, overly rational, and sometimes morally detached view of law.

But how well does Bentham’s theory hold up under moral scrutiny, practical application, and evolving legal thought?

This blog explores the main critiques of Bentham’s jurisprudence, evaluates his influence, and reflects on his lasting legacy in modern legal thought.

1. Bentham’s Core Philosophy: A Brief Overview

Bentham’s entire legal philosophy is rooted in the principle of utility. He believed that the purpose of law is to promote happiness and prevent pain. According to him, “Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure.” Every law should, therefore, be judged based on its capacity to produce more happiness than misery.

He rejected the concept of natural law and insisted that all law is man-made, or what he termed as positive law. Bentham’s focus was on the command of the sovereign, a precursor to the later theories of John Austin.

2. Major Critiques of Bentham’s Jurisprudence

Despite his significant contributions, Bentham’s theory has been criticized on several grounds – moral, practical, and philosophical. While Bentham’s utilitarianism was groundbreaking, it also sparked intense philosophical debate. The following critiques highlight the key tensions between utility and justice, reason and emotion, codification and flexibility.

A. Overemphasis on Quantitative Pleasure

Bentham treated pleasure and pain as measurable quantities, attempting to assess happiness through his famous hedonistic calculus. Critics, including John Stuart Mill, argued that this view reduces human happiness to a mere calculation of material pleasures. Mill later introduced the idea of qualitative pleasure, distinguishing higher pleasures (intellectual, moral) from lower ones (bodily or sensory).

Bentham’s approach thus appeared too mechanical and shallow to capture the moral depth of human satisfaction.

B. Neglect of Justice and Moral Values

Bentham’s utilitarianism often overlooks the principles of justice, fairness, and rights. For example, if punishing an innocent person could increase the overall happiness of society, Bentham’s logic would permit it. Critics argue that this leads to moral absurdities – sacrificing individuals for collective welfare.

Philosophers like Immanuel Kant sharply opposed this, asserting that individuals should be treated as ends in themselves, not as means to others’ happiness. Hence, Bentham’s model was seen as ethically deficient. This critique foreshadows later developments in rights-based theories, such as Rawls’ “justice as fairness,” which prioritize individual dignity over aggregate welfare.

C. Lack of Emotional and Social Considerations

Bentham viewed humans as rational agents motivated by pleasure and pain, ignoring emotions, moral sentiments, and social bonds that influence behavior. Thinkers like Edmund Burke and later sociologists criticized Bentham’s purely rational view of law as detached from the lived realities of human societies.

Law, they argued, is not only a tool for maximizing utility but also a cultural and moral institution shaped by history and emotion.

D. Simplistic View of Human Nature

Bentham’s utilitarian model assumes that humans always act in self-interest to maximize pleasure. However, this fails to recognize altruistic, spiritual, and moral motivations. Critics point out that many human actions are driven by conscience, duty, or love, not by the pursuit of personal happiness.

E. Mechanical Codification and Centralization of Law

Bentham was a strong advocate of codification – turning all laws into a written, rational, and accessible code. While this brought clarity and order, critics argue that excessive codification can make law rigid and inflexible. Law must evolve with society, and Bentham’s idea of a perfect, once-for-all code overlooked the dynamic nature of social change.

Moreover, his belief in a strong centralized legal authority ignored the value of judicial discretion and local customs. Modern legal systems have since sought a balance – embracing codification for clarity while preserving judicial discretion to adapt law to complex realities.

Bentham’s Jurisprudence: Contributions vs. Critiques

| Contribution | Critique |

| Law as a rational, scientific discipline | Overlooks moral complexity and emotional nuance |

| Codification for clarity and accessibility | Risks rigidity and ignores evolving social contexts |

| Utility as a moral standard | May justify unjust outcomes (e.g., punishing innocents) |

| Focus on consequences (felicific calculus) | Reduces morality to quantifiable pleasure/pain |

| Centralized legal authority | Undervalues local customs and judicial interpretation |

3. Evaluation of Bentham’s Influence

Despite the criticisms, Bentham’s contributions to jurisprudence remain monumental. His ideas laid the foundation for:

- Legal Positivism: Bentham’s distinction between what the law is and what it ought to be influenced John Austin, H.L.A. Hart, and modern positivists.

- Codification Movements: His advocacy for systematic codification inspired legal reforms in countries like France, India, and the UK. The Indian Penal Code (IPC) drafted by Lord Macaulay in 1860 bears Benthamite influence.

- Reform of Criminal and Civil Law: Bentham’s utilitarian principles promoted humane punishments, transparency, and efficiency in the justice system.

- Public Administration and Welfare Policies: His utilitarianism shaped public policy and economics, especially in designing welfare systems that prioritize collective benefit.

These reforms reflect Bentham’s enduring belief that law should be a tool for measurable social benefit – not a relic of tradition or divine command. In essence, Bentham converted jurisprudence into a science of law-making – empirical, rational, and socially oriented.

4. Critical Reflection and Legacy

Modern scholars recognize that while Bentham’s theory was not flawless, it marked a crucial transition from metaphysical to practical jurisprudence. His legal philosophy shifted focus from divine justice to social utility, urging lawmakers to evaluate every statute in terms of its social consequences.

However, his failure to balance utility with morality left a gap later filled by thinkers like Mill and Hart. Hart’s “The Concept of Law” refined Bentham’s positivism by including internal moral dimensions and the social acceptance of laws.

Bentham’s legacy lies not in his final conclusions, but in his methodology – his insistence that law must serve human happiness, be clear, and be accountable. His critical approach continues to influence debates on legal reform, human rights, and public welfare.

Can a legal system be both morally grounded and empirically driven? Bentham’s legacy invites us to explore this balance.

Conclusion

Jeremy Bentham’s jurisprudence stands as both a milestone and a mirror for modern law. While his utilitarianism sometimes oversimplified human morality, his vision of a rational, transparent, and welfare-oriented legal system remains deeply relevant. The true value of Bentham’s legacy lies not in the perfection of his ideas, but in the questions they provoke –

Should law serve morality or happiness?

Should justice be qualitative or quantitative?

In the end, Bentham’s critics did not destroy his philosophy; they helped it evolve. His utilitarianism, though imperfect, became the foundation for legal reforms across the world – proving that even critique can be the highest form of influence.

Enjoy the podcast of the blog:

References:

- Bentham, Jeremy. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789).

- Mill, John Stuart. Utilitarianism (1861).

- Hart, H.L.A. The Concept of Law (1961).

- Burns, J.H. Bentham and the Common Law Tradition. Oxford University Press, 1985.

- Twining, W.L. Theories of Law: Bentham, Austin, and Hart. Clarendon Press, 1980.

- Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice. Harvard University Press, 1971.

#JeremyBentham #LegalPhilosophy #Utilitarianism #Jurisprudence #LawAndMorality #LegalReform #LegalPositivism #BenthamCritique #PhilosophyOfLaw #Codification #LawBlog #HedonisticCalculus #BenthamVsMill #LawAndJustice #ImmanuelKant #Hart #Mill #Rawl

Discover more from Dr. Ganesh Visavale

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.