Can law be moral without invoking religion or natural rights? Bentham thought so – and built a system to prove it.

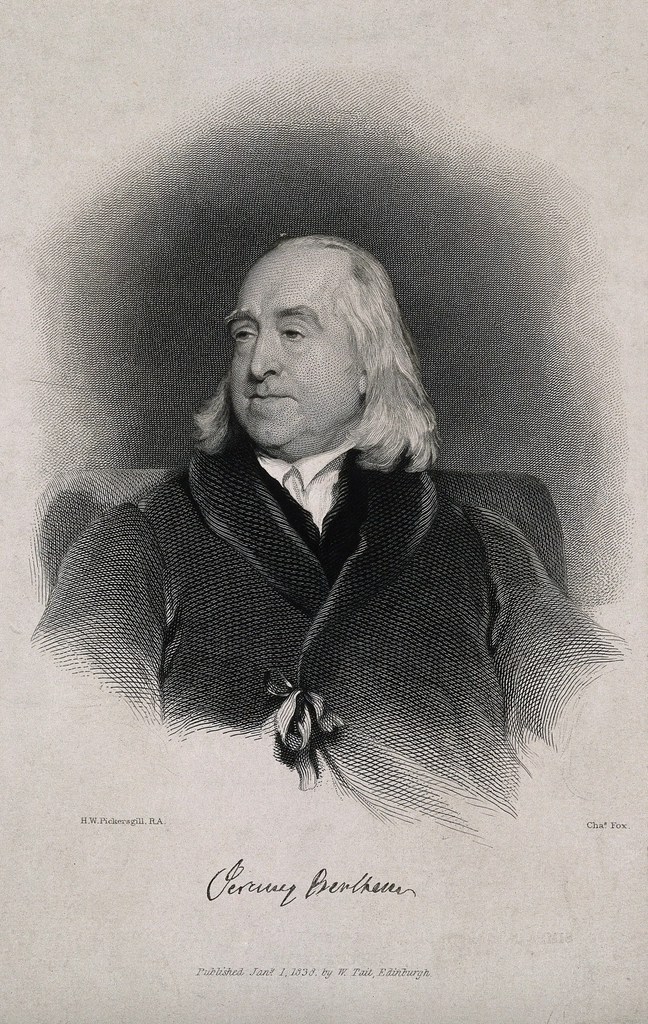

Jeremy Bentham, one of the most influential figures in legal philosophy, is best known as the founder of the school of legal positivism and the doctrine of utilitarianism. His ideas reshaped how law was viewed in the 18th and 19th centuries, emphasizing that the law should not be confused with morality or religion. Instead, Bentham proposed that the ultimate goal of law is to promote the greatest happiness of the greatest number – a principle that continues to influence modern legal systems worldwide.

In Bentham’s jurisprudence, the relationship between law and morality is distinct yet connected through the utilitarian lens. While he believed morality should guide legislation to achieve social happiness, he also maintained that law, as it exists, must be studied separately from moral ideals.

Bentham’s Concept of Law

Bentham defined law as “an assemblage of signs declarative of a volition conceived or adopted by a sovereign in a state, concerning the conduct to be observed in a certain case by a certain person or class of persons.”

This definition makes it clear that Bentham’s approach was positivist – he treated law as a command of the sovereign backed by sanctions. In this sense, the validity of law depends on its source (the sovereign’s authority), not its moral worth. A law could be good or bad, moral or immoral, yet it remained a law as long as it was duly enacted and enforced by the sovereign power.

Bentham thus separated “what the law is” (positive law) from “what the law ought to be” (morality or ethics). This separation was crucial in establishing jurisprudence as a scientific discipline – one that studies laws objectively rather than through moral or religious emotions.

Utilitarian Morality and the Purpose of Law

Though Bentham separated law from morality, he never denied the importance of moral reasoning in the creation of laws. His utilitarian principle – “the greatest happiness of the greatest number” – was his measure of moral rightness.

According to Bentham, every human action, including law-making, should be judged by its utility, meaning its ability to increase pleasure and decrease pain. Thus, while the existence of law was independent of morality, the evaluation of law was moral in a utilitarian sense.

For example, if a law leads to the welfare of the majority and reduces suffering, it is considered morally justified. Conversely, laws that create unnecessary pain or favor the interests of a few are immoral and must be reformed. In this way, Bentham provided a bridge between law as it is and law as it ought to be, using utility as the moral test.

Separation of Law and Morality

Bentham’s distinction between law and morality was a revolutionary move away from natural law theory, which claimed that moral principles form the basis of all valid laws. Bentham criticized natural law thinkers like Blackstone for mixing divine or moral standards with the legal system.

He famously referred to the idea of natural rights as “nonsense upon stilts.” For Bentham, law was not derived from God, nature, or conscience but from human will expressed through legislative authority.

In other words, morality may inspire lawmakers, but it cannot determine what the law is. This is the heart of Bentham’s legal positivism. Once a law is made, citizens must obey it, not because it is moral, but because it is commanded by a legitimate sovereign and backed by sanctions.

Bentham’s Critique of Natural Law and Morality-Based Systems

Bentham rejected the natural law concept that certain rights and laws exist inherently, independent of state authority. He believed such theories led to confusion, anarchy, and false expectations among people. Bentham argued that grounding rights in metaphysical notions invites legal instability. Without a sovereign authority to define and enforce rights, society risks devolving into subjective moralism rather than coherent governance.

He argued that moral reasoning based on abstract ideals like “justice” or “natural rights” is vague and subjective. Instead, he demanded measurable and rational standards – pleasure and pain – to assess both moral and legal rules. This measurable approach formed the basis of Bentham’s “felicific calculus,” a method to quantify the moral weight of actions based on their consequences.

For Bentham, moral and legal judgments should rely on calculable consequences, not divine or emotional reasoning. Bentham’s insistence on empirical reasoning marked a shift from deontological ethics to consequentialism, aligning legal norms with observable outcomes rather than abstract duties. Thus, utilitarian morality gave lawmakers a practical tool to craft laws based on real human happiness rather than metaphysical beliefs. Bentham’s commitment to utility extended beyond theory into personal legacy.

Jeremy Bentham’s preserved body, called the “Auto-Icon”, is displayed at University College London – fulfilling his wish to remain “useful” to society even after death!

Law as a Means to Achieve Moral Ends

Although Bentham separated law from morality conceptually, he viewed law as an instrument for achieving moral and social ends. The law should promote order, happiness, and welfare in society. Therefore, good laws are those that maximize pleasure and minimize pain for the community. This utilitarian metric provided lawmakers with a secular, rational basis for evaluating legislation – especially in pluralistic societies where moral consensus is elusive.

For instance, criminal laws are justified not because crime is morally wrong in a religious sense, but because crime causes pain – to victims and to society. Punishment, therefore, should only be as severe as necessary to deter wrongdoing, reflecting the principle of utility. Bentham’s views anticipated modern sentencing guidelines, which emphasize deterrence, rehabilitation, and proportionality over retribution.

This approach made Bentham one of the earliest advocates of rational criminal justice reform. He opposed excessively harsh punishments and emphasized proportionality – punish only as much as needed to prevent greater harm.

Comparison Table: Natural Law vs. Bentham’s Utilitarianism

| Aspect | Natural Law | Bentham’s Utilitarianism |

|---|---|---|

| Source of Authority | Inherent moral order; divine or rational principles beyond human legislation | Sovereign command; laws enacted by legitimate authority |

| Basis of Morality | Universal moral truths (e.g., justice, natural rights) | Consequences measured by pleasure and pain (principle of utility) |

| Legal Validity | Law is valid if it aligns with moral or natural rights | Law is valid if properly enacted, regardless of moral content |

| Practical Implications | Encourages moral critique of unjust laws; may lead to legal uncertainty | Enables rational lawmaking focused on social welfare and measurable outcomes |

Modern Relevance of Bentham’s Ideas

Bentham’s distinction between law and morality paved the way for modern legal positivists like John Austin and H.L.A. Hart. Today, most legal systems recognize this separation: laws are valid because of their proper enactment, not because they are moral. This analytical distinction – between what law “is” and what law “ought to be” – remains foundational in jurisprudence classrooms and judicial reasoning alike.

However, Bentham’s utilitarian moral framework also continues to influence public policy, lawmaking, and legal reforms, particularly in fields like criminal law, welfare legislation, and environmental regulation.

Influence on Modern Legal Systems

| Legal Domain | Natural Law Influence | Utilitarian Influence (Bentham) |

| Criminal Justice | Crime seen as moral wrongdoing; punishment reflects moral blame | Crime assessed by social harm; punishment aims at deterrence and proportionality |

| Constitutional Interpretation | Rights viewed as inherent and inalienable; judges may invoke moral principles | Rights justified by social utility; legal interpretation favors measurable outcomes |

| Legislative Policy | Laws must align with moral values or human dignity | Laws evaluated by cost-benefit analysis and impact on public welfare |

| Judicial Review | Courts may strike down laws violating moral or natural rights | Courts assess laws based on their practical consequences and societal benefits |

| Human Rights Debates | Emphasis on universal moral claims (e.g., dignity, freedom) | Emphasis on maximizing happiness and minimizing suffering across populations |

Laws are still evaluated based on their social utility and their impact on human happiness – a testament to Bentham’s lasting legacy.

Conclusion

In Bentham’s jurisprudence, law and morality are distinct but not divorced. Law, as a command of the sovereign, must be studied scientifically, while morality – through utilitarianism – provides the ethical foundation for creating just and beneficial laws. His philosophy teaches us that while moral sentiments should not dictate law, they should inspire lawmakers to design systems that maximize collective happiness. In this way, Bentham’s jurisprudence offers a dual lens: law as a technical system governed by rules, and morality as a compass guiding its evolution.

Bentham’s theory thus remains a cornerstone of modern jurisprudence, balancing the precision of legal positivism with the compassion of moral reasoning through the principle of utility.

References

- Jeremy Bentham, An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789).

- H.L.A. Hart, Essays on Bentham: Studies in Jurisprudence and Political Theory (1982).

- W. Twining, Bentham on Legal Reasoning (Clarendon Press, 1975).

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – “Jeremy Bentham.”

#JeremyBentham #LawAndMorality #LegalPositivism #Utilitarianism #Jurisprudence #PhilosophyOfLaw #NaturalLawVsPositivism #LegalTheory #BenthamJurisprudence #GreatestHappinessPrinciple #FelicificCalculus #CriminalJusticeReform

Discover more from Dr. Ganesh Visavale

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.