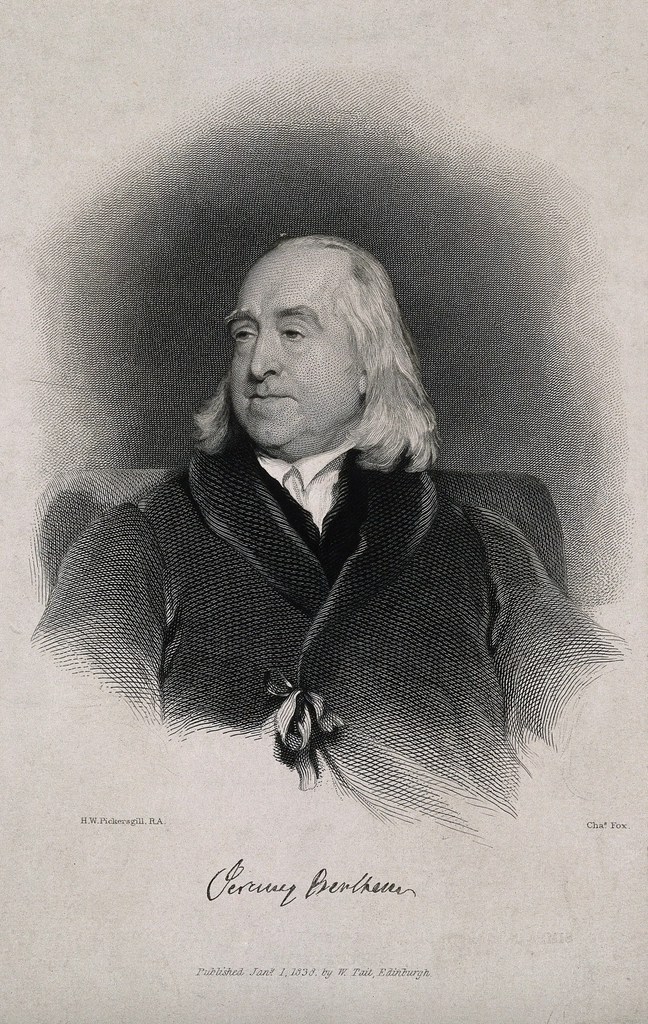

Jeremy Bentham, the English philosopher and founder of Utilitarianism, believed that the purpose of all laws and moral actions should be to promote the greatest happiness of the greatest number. But how can happiness – a deeply personal and emotional experience – be measured? Bentham answered this question through his innovative idea known as the Hedonic Calculus. This method provided a rational and almost mathematical way to evaluate human actions based on the amount of pleasure or pain they produce. Bentham introduced this idea in An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789), aiming to make moral reasoning as systematic as economics or jurisprudence.

This blog explores Bentham’s Hedonic Calculus, its factors, practical use, and its relevance to modern legal and ethical thought.

Understanding Bentham’s Theory of Utility

At the heart of Bentham’s philosophy lies the Principle of Utility, which holds that the moral worth of an action depends entirely on its utility, or its ability to produce happiness (pleasure) and reduce suffering (pain). Bentham rejected moral reasoning based on religion, custom, or abstract notions of “natural rights.” Instead, he sought to establish a scientific basis for ethics and law, rooted in human experience and measurable consequences. He envisioned lawmakers as moral accountants, tasked with calculating the social balance sheet of pleasure and pain.

For Bentham, pleasure and pain were the two sovereign masters governing all human behavior. Every law, action, or policy could be justified only if it tended to increase overall happiness and reduce suffering. However, this approach required a systematic way to compare and measure different pleasures and pains – thus came the idea of the Hedonic Calculus.

What is the Hedonic Calculus?

The Hedonic Calculus (also known as the felicific calculus) is Bentham’s attempt to quantify pleasure and pain. He proposed that before taking any moral or legal decision, one should measure the expected happiness or suffering resulting from it using seven key criteria.

This was not meant to be a perfect mathematical formula, but rather a rational guide to help lawmakers and individuals make decisions that maximize overall happiness. Bentham acknowledged the subjective nature of pleasure but insisted that structured reasoning could still guide better decisions than intuition or tradition.

The Seven Factors of the Hedonic Calculus

Bentham’s seven criteria were designed to help assess both individual and collective consequences of actions. They appear in Chapter IV of his Principles of Morals and Legislation. Bentham listed seven measurable dimensions of pleasure and pain:

- Intensity – How strong is the pleasure or pain?

A mild satisfaction from helping someone might rank lower than the intense joy of saving a life. - Duration – How long will it last?

A brief excitement may be less valuable than a lasting sense of peace or well-being. - Certainty (or Uncertainty) – How likely is it to occur?

A probable pleasure may be preferred to an uncertain one, even if the latter could be greater. - Propinquity (or Remoteness) – How soon will it occur?

Immediate pleasure may have a stronger motivating force than distant rewards. - Fecundity – Will it lead to more pleasures in the future?

For instance, education may bring pleasure now and also lead to lifelong satisfaction. - Purity – Will it be followed by pain, or is it free from harmful consequences?

A pleasure that causes later pain (like drug use) has less value than one without such after-effects. - Extent – How many people will be affected?

A decision that benefits many has greater moral value than one that benefits only a few. This factor reflects Bentham’s commitment to democratic ethics – the happiness of many outweighs the happiness of few.

Bentham believed that by weighing each of these factors, one could calculate the net pleasure or pain produced by an action.

Jeremy Bentham’s preserved body, known as his “Auto-Icon,” is still displayed at University College London – an embodiment of his belief that even in death, one can serve the happiness of others through education.

Applying the Hedonic Calculus in Law and Society

Bentham’s Hedonic Calculus had a profound influence on legal and political philosophy. He argued that lawmakers should use the principle of utility to design policies and punishments that promote public happiness. Bentham’s utilitarianism laid the groundwork for consequentialist legal theory, where outcomes – not intentions – determine the justice of laws.

For example:

- In criminal law, punishment should not be based on revenge but on its utility– i.e., the prevention of future crimes and deterrence of offenders. The pain of punishment should only exceed the pleasure gained from committing the crime.

- In public policy, governments should evaluate laws based on their overall contribution to social welfare rather than moral traditions or religious codes.

Even modern legal reforms – like cost-benefit analysis, welfare economics, and public health policymaking – reflect Bentham’s utilitarian roots. When governments assess policies through measurable impacts (such as reduction in poverty, increased life satisfaction, or economic gain), they echo Bentham’s calculus of happiness.

Criticism and Limitations

While revolutionary, Bentham’s Hedonic Calculus has faced criticism for oversimplifying human emotions. Critics argue that happiness cannot be precisely measured or compared across individuals. For example, the joy of a child receiving food cannot be quantified against the pleasure of a billionaire buying a yacht.

Philosophers like John Stuart Mill, Bentham’s disciple, refined utilitarianism by distinguishing between higher and lower pleasures. Mill argued that intellectual and moral pleasures are of greater value than mere physical gratification—a nuance Bentham’s purely quantitative approach missed.

Additionally, ethical critics suggest that Bentham’s system could, in some cases, justify morally questionable acts (like punishing an innocent person) if it increases total happiness. This is known as the “tyranny of the majority” problem — where aggregate happiness might override individual rights. Critics like Rawls and Nozick later challenged this implication. Despite these flaws, Bentham’s calculus remains a landmark in the history of moral philosophy and social reform.

Relevance Today

In the modern world, Bentham’s Hedonic Calculus finds echoes in economics, psychology, and law.

- Behavioral economists use similar models to measure consumer satisfaction and well-being.

- Policymakers rely on data-driven approaches like the Happiness Index and Gross National Happiness (GNH) to assess progress beyond GDP.

- Legal theorists continue to apply utilitarian logic in sentencing, taxation, and human rights debates.

Bentham’s effort to quantify happiness – though imperfect – laid the foundation for a rational, evidence-based approach to ethics, law, and governance. Though Bentham’s calculus is rarely used in its original form, its spirit lives on in tools like cost-benefit analysis, impact assessments, and behavioral metrics.

Conclusion

Bentham’s Hedonic Calculus stands as one of the most ambitious attempts to bring scientific precision to moral reasoning. Though it cannot measure happiness with mathematical accuracy, it encourages rational deliberation, empathy, and the pursuit of collective welfare. In a world still grappling with inequality and ethical dilemmas, Bentham’s principle reminds us that the true purpose of law is not authority – but happiness.

Also Read:

Bentham on Punishment: When Pain Becomes Justified

The Principle of Utility: Bentham’s Greatest Happiness Formula

Jeremy Bentham: The Architect of Utilitarian Jurisprudence

References:

- Jeremy Bentham, An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789).

- John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism (1863).

- H.L.A. Hart, Essays on Bentham: Jurisprudence and Political Theory (1982).

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – “Jeremy Bentham.”

- Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice. Harvard University Press (1971).

#JeremyBentham #HedonicCalculus #Utilitarianism #LegalPhilosophy #LawAndEthics #Jurisprudence #HappinessIndex #PhilosophyOfLaw #BenthamTheory #MoralPhilosophy #PublicPolicy #LegalStudies #LawStudents #EthicalDecisionMaking

Discover more from Dr. Ganesh Visavale

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.