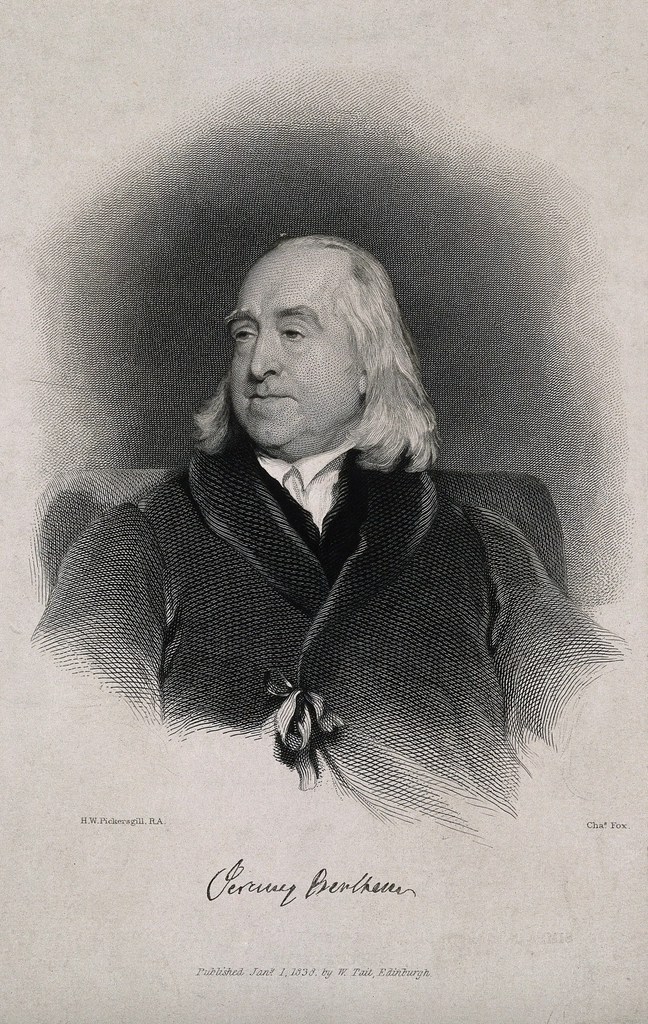

Jeremy Bentham, one of the greatest legal philosophers of the 18th century, is best remembered for his principle of utility – that all laws and actions must aim to achieve the greatest happiness of the greatest number. Yet, there is one question that challenges this principle more than any other:

Can inflicting pain ever be justified?

This question led Bentham to formulate one of his most influential and practical doctrines – his theory of punishment. Bentham’s approach was neither sentimental nor vengeful; it was utilitarian, meaning he saw punishment as a tool of social reform, not retribution. Bentham believed that punishment must be evaluated like any other social institution – by its consequences.

He asked: Does it do more good than harm?

The Paradox of Punishment

At first glance, punishment appears to contradict Bentham’s fundamental idea. If the aim of law is to maximize happiness and minimize pain, then punishment – which by nature inflicts pain – seems unjust.

Bentham acknowledged this paradox openly:

“All punishment in itself is evil.”

This stark admission appears in Bentham’s Principles of Penal Law, where he emphasizes that punishment must always be scrutinized through the lens of utility. However, he added a vital qualification – punishment becomes justifiable only when it prevents greater harm or promotes greater happiness for society. In other words, pain (punishment) is acceptable if it reduces more pain in the long run – such as by deterring crime, protecting society, or reforming the offender.

When Is Punishment Justified?

Bentham laid down clear conditions for when punishment is warranted. According to him, punishment should be applied only when it is useful – that is, when it serves a greater social purpose. In An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, Bentham outlines specific scenarios where punishment fails the utility test.

He listed four cases where punishment is not justified:

- When it is groundless –

If no offence has been committed, punishment serves no purpose. - When it is inefficacious –

If the punishment cannot prevent the offence (for example, punishing the insane), it is useless. - When it is unprofitable –

If the pain caused by punishment exceeds the benefit gained, it should be avoided. - When it is needless –

If the offence can be prevented by less painful means, punishment should not be used.

These principles reveal Bentham’s rational and humane approach. Punishment was not a matter of vengeance or moral outrage, but of social utility.

The Purpose of Punishment

For Bentham, the end goal of punishment was deterrence – to discourage future offences. He divided its functions into three key purposes:

- Deterrence – Preventing both the offender (specific deterrence) and others (general deterrence) from committing crimes.

- Reformation – Correcting the offender’s behavior through education, discipline, or rehabilitation.

- Incapacitation – Protecting society by restraining offenders who may harm others.

Bentham rejected the retributive theory of punishment (the idea that wrongdoers deserve to suffer). He argued that retribution is emotionally satisfying but socially wasteful – it does not prevent future harm and often perpetuates cycles of suffering. Instead, he emphasized preventive justice – law should prevent crimes before they occur, and punishment should serve as a rational tool to that end.

Proportionality and Certainty

Bentham was one of the earliest thinkers to insist that punishment must fit the crime – not in terms of moral desert, but in terms of utility.

He outlined several guidelines for legislators:

- Punishment should be just enough to outweigh the pleasure derived from the crime.

- The certainty of punishment is more effective than its severity. Bentham wrote, “The more certain the punishment, the less need for it to be severe.” This insight influenced modern criminology and sentencing guidelines.

- Laws should be clear and predictable, so individuals can foresee the consequences of their actions.

In short, punishment must be measured, predictable, and socially beneficial, never excessive or vengeful.

Humanitarian Reform through Law

Bentham lived at a time when punishments were often cruel and arbitrary – public executions, torture, and imprisonment under inhuman conditions were common. He condemned these practices as irrational and counterproductive. Bentham’s critique extended to the arbitrary nature of common law, which he saw as opaque and inaccessible. He advocated for codification to ensure transparency and fairness.

His utilitarian perspective inspired major legal reforms in England and beyond:

- Abolition of torture and mutilation as legal penalties.

- Emphasis on prison reform and humane treatment of inmates.

- A scientific, codified approach to criminal law.

Bentham’s vision of rational, proportional, and humane punishment laid the groundwork for modern criminal justice systems that prioritize rehabilitation over cruelty.

Bentham’s Legacy in Modern Law

Modern legal systems still reflect Bentham’s influence:

- The idea of “least necessary punishment” guides contemporary sentencing.

- Deterrence and reform remain central goals of penal policy. His utilitarian calculus continues to inform debates on restorative justice, sentencing proportionality, and the ethics of incarceration.

- His utilitarian balance – between the rights of individuals and the welfare of society – continues to shape debates on capital punishment, prison reform, and criminal justice ethics.

Bentham taught that justice is not about revenge but rational compassion – a concept that continues to resonate in modern jurisprudence.

Conclusion

For Bentham, punishment was a necessary evil – justified only when it prevents greater harm and promotes the greater good. He replaced moral vengeance with pragmatic reason, showing that the true purpose of law is to protect happiness and prevent suffering.

Even centuries later, his insight remains clear:

“Punishment should never be inflicted merely because it is deserved, but only because it is useful.”

📘 Did You Know?

Jeremy Bentham was one of the first philosophers to argue for prison design reform – he even drafted a plan for a “Panopticon Prison,” where prisoners could be observed at all times to encourage discipline and moral reform.

Also Read:

The Principle of Utility: Bentham’s Greatest Happiness Formula

Jeremy Bentham: The Architect of Utilitarian Jurisprudence

📚 References

- Jeremy Bentham, An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789).

- H.L.A. Hart, Essays on Bentham: Studies in Jurisprudence and Political Theory (1982).

- Gerald J. Postema, Bentham and the Common Law Tradition (1986).

- Philip Schofield, Utility and Democracy: The Political Thought of Jeremy Bentham (2006).

#JeremyBentham #PunishmentTheory #Utilitarianism #LegalPhilosophy #Jurisprudence #CriminalJustice #LawAndSociety #LegalRemedy #BenthamSeries

Discover more from Dr. Ganesh Visavale

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

1 Comment